Loading data from multiple regions of multiple upstream web services at once, invisibly live updating in the background – through a consistent interface allowing simple feature development.

My team develops the Rackspace Open Cloud Control Panel. Since its inception two years ago we have gone from greenfield application development with separate frontend (JavaScript) and backend (Python) teams to an almost entirely frontend application. At my last count, our codebase has around 190k lines of JavaScript.

Our project was designed with a modern web experience in mind: a single-page application where a user could intuitively manage their infrastructure and get on with their day. Our starting point was the Google Closure Library, which provides a number of native button, menu, and dialog widgets. We spent a lot of time extending these to meet the desired user experience. For example, we built an ActionMenu class that is a subclass of goog.ui.Menu for the desired experience of performing actions on a resource from a product list or detail page. View development for our application mostly involves writing our own subclasses of goog.ui.Component that generated the correct markup and had the right DOM event behavior.

I don’t want to reduce the amount of effort we spent on this: it was a lot of important work, a lot of hours, and just like any other project, a lot of frustrating defects. However, the Closure Library was aimed at the same problems that we were solving: creating interactive widgets with HTML and JavaScript. Most of the team’s learnings in this area were about how to work better with the library (including some rather technical information), rather than confronting any new problems.

In constrast, we faced unique problems in loading data from our model layer into to our views. In this post I’ll going to describe the architecture that we ended up with. The end result supports resources of many different types from many different upstream APIs through a consistent interface that hides the complicated problems of data loading and updating from day-to-day development tasks.

What We Needed

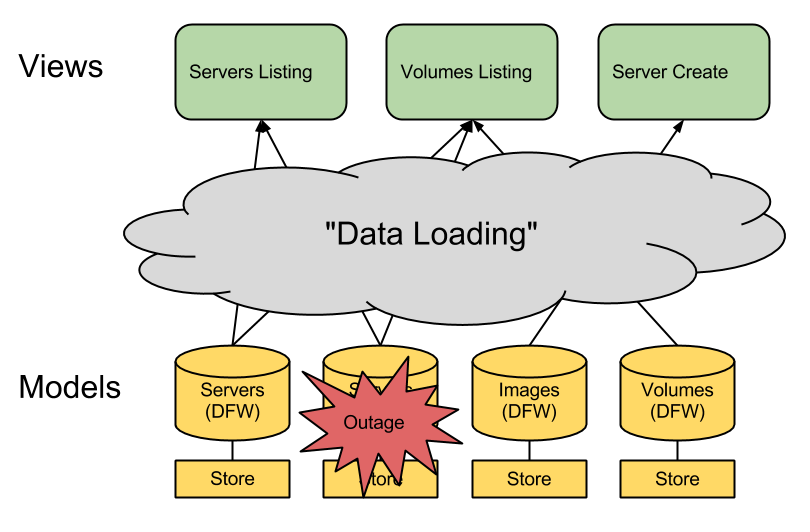

Data Loading is the process by which data makes it from the model layer to the view layer. Depending on which flavor of MV* you prefer this is done differently but the problem is a general one and not dependent on application structure. Application views potentially need data from multiple upstream APIs. If a resource is not available, a view should display a partial or total error state. Data displayed in a view should be updated invisibly in the background on a set interval that is potentially different for each type of resource.

The Open Cloud Control Panel is built on REST APIs; the same APIs that Rackspace customers are able to programmatically access through curl, Rackspace SDKs, or multi-cloud SDKs such as jclouds, libcloud, and fog. All of this data is associated with a specific upstream API. Certain resource types have data available in multiple regions. For example, the Servers API is a multi-region API with different resources between Dallas, Chicago, London, and Sydney endpoints; each of these has servers (virtualized compute instances), images (snapshots of a machine that can be turned into a running instance on demand), and flavors (a list of server configuration presets such as RAM and Disk). In contrast the Cloud DNS API is a global API with only one region and only one top-level resource.

While these APIs have good uptime, our application reflects the uptime of all of these APIs together. Should one become unavailable, it’s our job to make sure that a failure from one API does not become a global failure of the entire Control Panel.

An additional complication is that our application doesn’t have an intelligent backend: all the data from these upstream APIs is passed to JavaScript through XMLHttpRequest without transformation. There isn’t a backend layer that aggregates this data together and handles failure. All of the instrumentation of data from these upstream APIs is done in our JavaScript model layer. (While I’m presenting the absence of an intelligent backend as a technical challenge, this was by far the best design choice that we made as a team and I want to dig into it in a future post.)

Providers

To handle the concept of unique upstream APIs, every model and collection has a Provider object associated which it. A provider uniquely identifies an upstream API by region (DFW, ORD, LON) and service type (compute, dns, loadbalancer).

// fails! cannot determine which API to request data from without a provider!

servers = new Servers();

servers.fetch();

> 'Uncaught exception: must set provider to save data'

// works -- makes POST request to upstream DFW compute API

server = new Servers();

server.setProvider(getProvider('compute', 'DFW'));

server.save();

Similarly regions are built into different views: when you are viewing a server details, you need information from the URI to determine whether you should make requests to Dallas, Chicago, or London.

provider = getProvider('compute', 'DFW');

// argument needs a provider object to make a request to the correct

// upstream API

navigateToDetails(provider, server.get('uuid'));

Not all upstream APIs have an associated region. The Cloud DNS API has a single region; there is only one provider object associated with this API.

Failure Handling

As a service oriented application, the Control Panel doesn’t own much data. Upstream APIs determine much of the content that is shown, and implement certain complicated validation rules that we do not duplicate on the application level (for example, enforcing password complexity requirements for compute infrastructure).

As a result, when you persist data through the model layer, it must wait for a 200 OK or 202 Accepted from the upstream API before changing the application state. The concept of upstream success or failure is a first-class behavior in the application and is built into the model layer.

server.save();

goog.events.listen(

server,

events.SUCCESS,

function (e) {

var rootPassword = e['rootPassword'];

navigateToDetails(server.getProvider(), e['uuid']);

// navigate to a different page and display the password in a 1-time dialog

});

goog.events.listen(

server,

events.ERROR,

function (e) {

var message = e.getMessage();

// display the message on the page

});

In contrast, when you build an application in front of a database that you totally own, you can reasonably expect most requests to succeed. This isn’t to say that failure handling isn’t important, but the scale that we operate at (over 75 requests per second through our upstream API servers at peak) means that we must design for failure. The site must still work correctly if a failure occurs and messaging this failure correctly is absolutely critical.

View Lifecycle

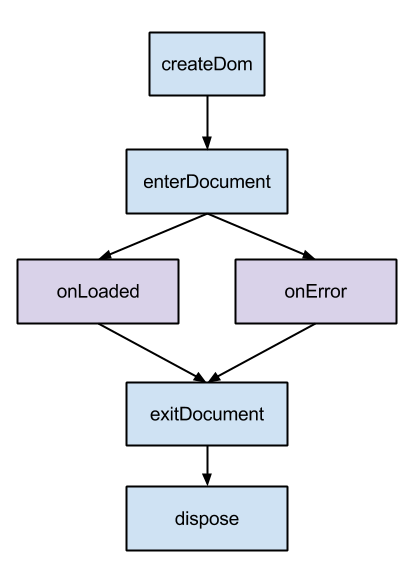

Our main approach to a data loading interface was extending our view’s lifecycle. As an example, the goog.ui.Component class in the Closure Library has a strict lifecycle: createDom is called to create a widget’s markdown, enterDocument is called when it is actually placed into the document, exitDocument when it is removed, and dispose when it is finally discarded. Any subclass of goog.ui.Component can add behavior at each of these lifecycle points by overriding any of these base functions.

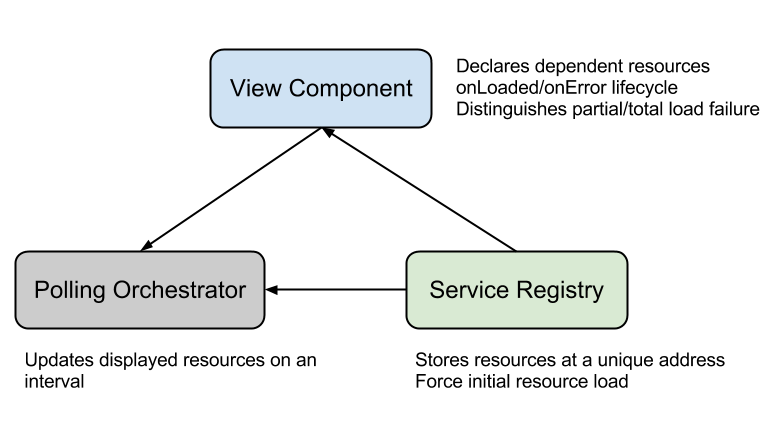

To handle data loading as part of view lifecycle, we wrote a ViewComponent class, a subclass of goog.ui.Component, with two new lifecycle function. Dependencies for data loading are declared in enterDocument. The onLoaded function is called when data was ready to be displayed by the view, while the onError function is called if some of the requested data failed to load.

Resources and Addresses

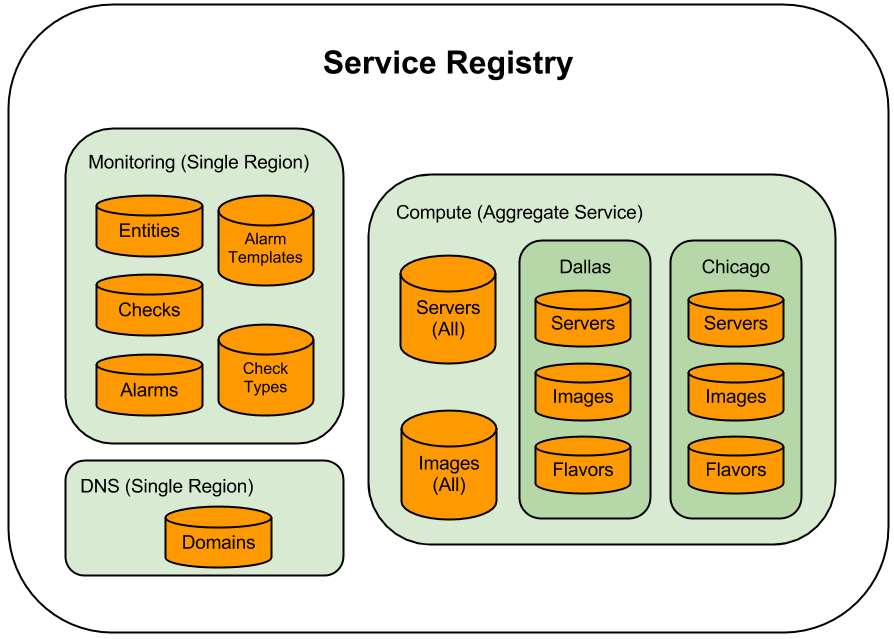

To specify which data views need to display correctly, views request resources. Resources are individual collections and models that are either associated with a provider (“compute DFW”) or a service type (“compute”). Provider-specific resources represent all the data of one type (“Cloud Servers”) from one datacenter (“Dallas (DFW)”). Resources associated with a service type (“compute”) are aggregate resources: these are read-only resources that group together all resources of a certain kind and are used to display product listing (“here are all of your Cloud Servers”).

Each resource has an address: a list that uniquely identifies it that includes either a provider or a service type. For example, suppose Cloud Servers are stored in the class data.Servers. The following are unique addresses in our application:

// address for servers in DFW datacenter

[ dfwProvider, data.Servers]

// address for an individual server in the DFW datacenter

[ dfwProvider, data.Servers, uuid ]

// address for all servers across all datacenters

[ "compute", data.Servers ]

There’s nothing special about using the class as part of the address. Our addresses could easily be adapted to strings like "compute/servers" and "compute/dfw/servers": all that matters is that an address uniquely identifies a resource.

Services and Modules

Services are contain all the data associated with an individual provider; their main purpose is to associate requests for resources at an address with the resource itself. For example, a Compute Service may register that it knows about data.Servers, data.Images, and data.Flavors collections.

Aggregate services contain data associated with an individual service type and contain read-only aggregate resources. For example, the aggregate compute service knows the address for data.Servers, a collection that contains all the models that are in each compute service’s data.Servers collection.

To keep our JavaScript files small, services are only created on demand: requesting data from a new provider or a compute type will first load a new JavaScript module, which on loaded, registers how to create the service. The step looks like:

- Request comes in for the

["compute", data.Servers]address - The service associated with this address is not loaded yet.

- The “compute” service type requires loading the

compute_serviceJavaScript module. This module begins loading. - The

compute_servicemodule has finished loaded; after load, a compute service associated with every region a custom has access to (Dallas, Chicago) created. - The aggregated collection containing the servers from every region is returned.

Before we added this level of indirection, all of our JavaScript classes had a goog.require dependency to the data layer of every other product. Because of this, our Cloud Servers section could theoretically have called into the data layer for Cloud Files, a mostly-independent section of our application, meaning that any built JavaScript file that included one needed to include the other. This caused our built JavaScript files to get larger than we would have preferred. By adding module loading as a dependency in our data layer, we severed this dependency, allowing us to load smaller files that only required what they needed.

The ViewComponent accesses the hierarchy of aggregate services, services, and the resources that they contain through the ServiceRegistry class.

Forcing Resource Load with Deferreds

The main function of the ServiceRegistry is looking up resources by address. The second function is to force the load of a resource through the require function. require takes a list of addresses and two callbacks, onLoaded and onError, and invokes the appropriate callback based on whether or not the resources loaded successfully.

Here’s some pseudocode for how this occurs: the main class we used for this is the Closure implementation of goog.async.Deferred, based on the MochiKit implementation.

/**

* Wait for all resources at the list of address to load. If everything

* succeeds, invoke onLoaded; if not, invoke onError.

*

* @param {Array.<Address>} addresses

* @param {function ()} onLoaded

* @param {function ()} onError

*/

data.ServiceRegistry.prototype.require = function (addresses, onLoaded, onError) {

var deferreds, deferredList;

deferreds = [];

goog.array.forEach(addresses, function (address) {

deferreds.push(this.getDeferredForAddress_(address));

}, this);

// on all succeeded, call onLoaded

// on any failure, call onError

deferredList = new goog.async.DeferredList(deferreds);

deferredList.addCallback(onLoaded);

deferredList.addErrback(onError);

// return the deferred so it can be cancelled (if necessary)

return deferredList;

};

/**

* Return the deferred associated with loading the resource stored at the

* given address.

*

* @private

* @param {Address} address

* @return {goog.async.Deferred}

*/

data.ServiceRegistry.prototype.getDeferredForAddress_ = function (address) {

var resource, deferred, handler;

// not shown: loading additional modules as part of the initial require call

resource = this.getDependency(address);

deferred = new goog.async.Deferred();

// if the resource has already loaded, we don't need to wait for this deferred

if (resource.isLoaded()) {

deferred.callback();

return deferred;

}

handler = new goog.events.EventHandler();

handler.listen(

resource,

data.SUCCESS,

function () {

handler.dispose();

deferred.callback();

});

handler.listen(

resource,

data.ERROR,

function () {

handler.dispose();

deferred.errback();

});

// forces the resource to update if it not currently updating -- this avoids

// multiple XMLHttpRequests being created for multiple resource requests

if (!resource.isLoading()) {

resource.fetch();

}

return deferred;

};

A Uniform Interface for Subclasses

ViewComponent subclasses add dependencies on resources through the addDependency method. Each call to addDependency adds a new address to the list that is eventually forced to load through the Service Registry require function. Once loaded, a ViewComponent can retrieve the dependency through getDependency, which passes an address to the Service Registry and requests the resource associated with that address.

/** @inheritDoc */

servers.DetailsView.prototype.enterDocument = function () {

goog.base(this, 'enterDocument');

// request a model from the servers collection

this.addDependency(

this.provider_,

data.Servers,

this.uuid_

);

};

/** @inheritDoc */

servers.DetailsView.prototype.onLoaded = function () {

goog.base(this, 'onLoaded');

// the model is ready and can be used now!

this.server_ = this.getDependency(

this.provider_,

data.Servers,

this.uuid_

);

this.renderServer();

};

It is not safe to request resources before onLoaded as the module associated with the resource may not even have been called.

Aggregate Dependencies and Failure

Certain views require all data from a service type (e.g. “compute”, “databases”) before being able to be rendered. As mentioned above, aggregate resources have an address associated with the compute type; however, these aggregate resources are “read only” and cannot be fetched like normal resources as there is no one XMLHttpRequest to make that will load all of this data.

Views that need data from “all regions” use addAggregateDependency: this calls through all regions and adds the appropriate resources as dependencies to be loaded. If everything loads as expected, this behaves as normal and this data will be available to be rendered by the view.

/** @inheritDoc */

servers.ListView.prototype.enterDocument = function () {

goog.base(this, 'enterDocument');

this.addAggregateDependency(

"compute",

data.Servers

);

};

/** @inheritDoc */

servers.ListView.prototype.onLoaded = function () {

this.table_.displayCollection(this.getDependency(

"compute",

data.Servers

));

};

However, if a resource fails to load, custom onError logic determines whether the failure is localized to an individual region. If we are attempting to load all servers, but DFW is available and ORD is not, this logic detects that the failure is isolated to a specific region, allowing the view to display the data that did end up loading and even potentially show a message that the customer’s resources are only partially available.

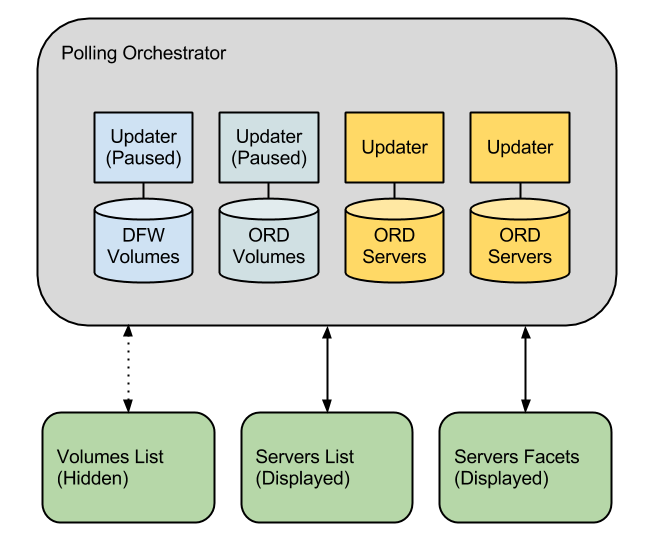

Updating Resources

Once a resource is displayed on the page, we update it on a certain interval as long as it is user visible. The PollingOrchestrator class keeps track of the resources requested by every displayed view. As long as a resource is displayed, it is updated on a timer in the background. Because all ViewComponent subclasses register which resources are required and are being displayed through their addDependency calls, this happens invisibly without writing any extra code.

On onLoaded, a ViewComponent registers the resources it is using with the PollingOrchestrator. The PollingOrchestrator class determines which updating strategy it should use for each resource (should it update? how frequently should it update?) and begins polling that resource. If a user navigates to a different page where this resource is no longer displayed by any view, the polling pauses until it is requested again.

We instrumented our Updater classes not to trigger the next update when the page is not visible using the Page Visibility API. If it would trigger the next update it is instead waits for the page to become visible using the visibilitychange event. On visible, all the updates fire again, meaning that when a customer switches back to a hidden tab, they will immediately see the current state of their resources.

Conclusion

Data loading was (and still is) a challenging problem in our application. Over the last two years we had long discussions as a team about the best way to get data into our views. Concepts like aggregate resources initially had amazingly complicated solutions. Each application did data loading a little differently, meaning that if you went from the Cloud Servers application to the Cloud Load Balancer application, you might see a set of similar but subtly different (in dangerous ways!) code patterns. We started by storing data in our views, but needed to stop that when there were too many different kinds of resources. We then moved to “god” objects that would be passed between views and store both regional and aggregate collections – the foundation of the existing “service” concept today. This ran into a number other problems and we had to back out this pattern quickly after it was implemented. Throughout it all polling was a persistent pain, requiring custom logic that was either instrumented on the app level or in an individual view.

The real success of this code architecture is that a set of very complicated problems have been made invisible to every-day feature development. The ViewComponent and ServiceRegistry classes form an abstraction layer that it isn’t often necessary to peek beneath and most of the time everything “just works” regarding getting data into a view to render data or make a decision about how to display it. Of course our challenge is now explaining this set of concepts that are alien to everyone’s day-to-day, but this is a problem with all abstractions!

It’s one thing to describe an architecture that works once you completely understand the problem, but how do you even know what problem you should be solving? Given the problem statement I wrote at the start of this post, we probably would have come up with something similar to our current solution, but without coding smaller attempts, it wouldn’t have been possible to know what our data loading problems even were, or what solution would work or not work. One of the great challenges in software development is discovering the right problem to solve and this only comes through experiencing failure. In my next post, I’ll dig through what led us towards our current data-loading architecture.