Update (06/25/2014): Github has built this into their web UI!

You don’t need to follow these steps any more. However, if you want to learn the git-fu that lets you do it yourself – go ahead!

My team uses Git and Github for all its development. This means I probably spend 1-2 hours a day interacting with the Github website, making comments on pull requests, making branches, and pruning our wiki.

Once code has been merged into our master branch, it goes through

our continuous integration process, which requires that it pass all

unit tests, integration tests, and system-level tests.

Sometimes after a pull request is merged, one of these testing levels fails, meaning that the continuous integration process is broken and needs to be fixed immediately. Given the situation where something is broken, there are two approaches: fix it or revert your work.

I prefer to always revert and get master back to a clean state –

something was missed before that initial merge and we need to make

sure that we apply the right fix. Every other developer on the team

(we have around 20) is blocked when master is failing tests and it

makes us unable to respond to critical defects that might have arisen in

production and require a quick solution.

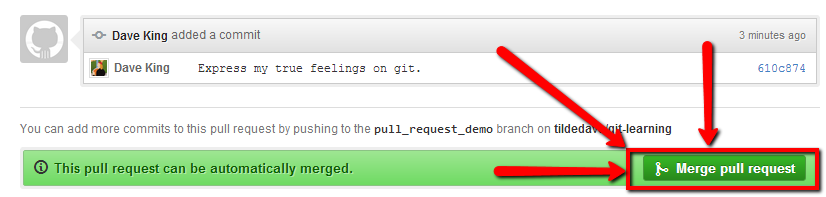

Step 1: Always Use the Green Button!

This following advice will not work if you do not use the Github green button to merge your pull requests. To make everything easier, you should always use the green button!

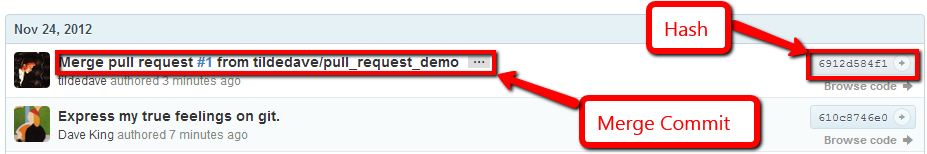

Step 2: Revert the Pull Request

To revert a pull request, the first thing you need to do is find the merge commit that the green button created. It’s highlighted in the following picture:

Here the hash 6912d584f1 is the merge commit: it records that the

branch tildedave/pull_request_demo was merged into master from Pull

Request #1. This is the commit hash we’re going to revert.

My recommended workflow is to create a new branch and revert this

commit in a new branch. The reason for this is that on a team with a

lot of developers, you rarely want to directly modify master.

# Always be current on your remote's origin master before doing anything!

> git checkout master

> git pull --rebase origin master

# Create a new branch

> git checkout -b revert_pull_request_1

Switched to a new branch 'revert_pull_request_1'

# Need to specify -m 1 because it is a merge commit

> git revert -m 1 6912d584f1

Finished one revert.

[revert_pull_request_1 cf09b44] Revert "Merge pull request #1 from tildedave/pull_request_demo"

2 files changed, 1 insertions(+), 4 deletions(-)

delete mode 100644 this-is-also-a-test-file

# Push your changes

> git push origin revert_pull_request_1

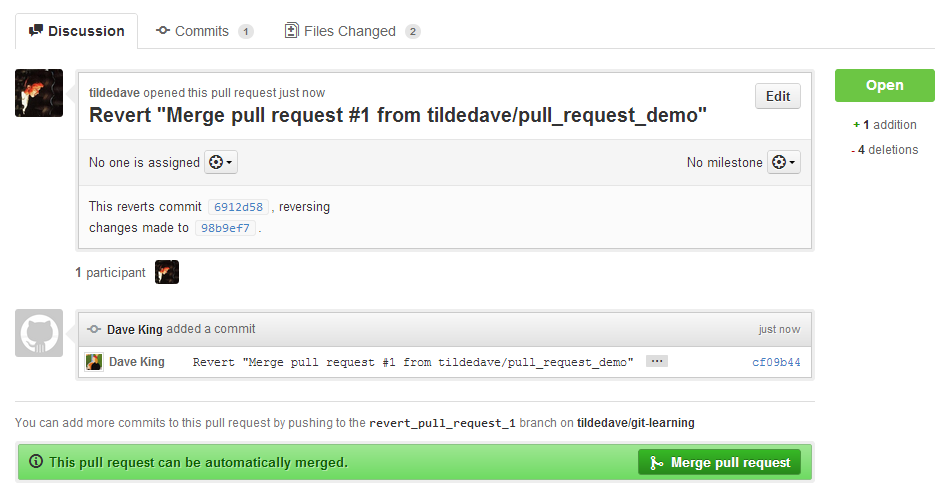

The next step is to merge your branch that reverts the pull request.

Like every other change to master, this should be done through

Github with the green button.

Once this has been merged, the original pull request has been reverted.

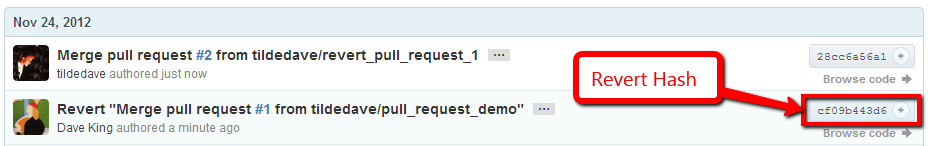

Step 3: Fix the Original Pull Request

After the original pull request has been reverted, we must fix it.

The first thing we do here is to find the revert hash – this is the

commit hash created by executing the git revert above.

The revert hash was given in the command results above, but you can also find it through Github by looking at the commit right before your merged revert pull request.

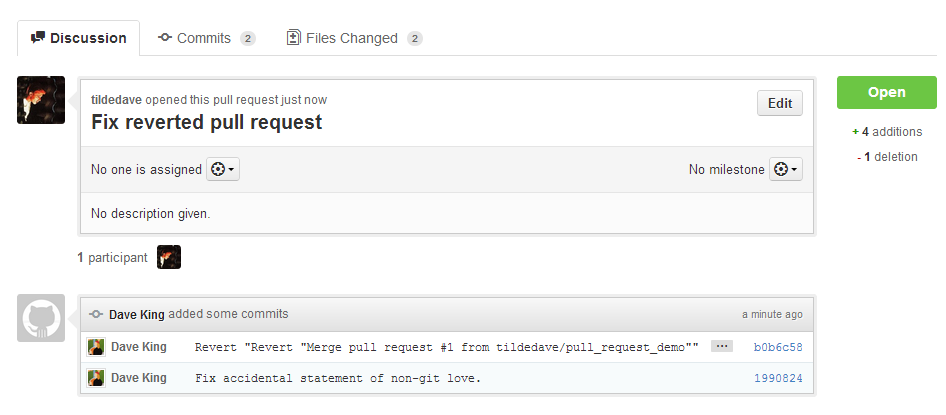

Now that we have the revert hash, we can make a new branch and revert the revert, then add additional commits to fix whatever was wrong with the branch.

> git checkout master

> git pull --rebase origin master

> git checkout -b fix_reverted_pull_request_1

> git revert cf09b443d6

Finished one revert.

[fix_reverted_pull_request_1 b0b6c58] Revert "Revert "Merge pull request #1 from tildedave/pull_request_demo""

2 files changed, 4 insertions(+), 1 deletions(-)

create mode 100644 this-is-also-a-test-file

What if bad code is already in production?

My team practices continuous delivery, meaning that we deploy 4-5 times a day at minimum. In the event that something makes it past our suite of tests and gets into production, we need to follow up to make sure that this gets fixed as fast as it went wrong.

Here there are two options and it’s a little fuzzier than the above process. The main thing that affects this is whether or not there is a data ramification of rolling back.

If a change during the day has affected data storage formats or protocols between distributed systems, I prefer to roll forward, because in general it’s hard to understand the consequences of old code and new data.

Otherwise it is safe to deploy old code. Whether or not this should be done is totally dependent on the criticality of the issue and the speed that an issue can be resolved.

Summary

- Always make changes to

masterin the same way. - When detecting a problem, always follow the same procedure to roll code back.

- When working on a team with other developers, make sure that you are not blocking other people’s work.

- If bad code has already made it to production, roll the code forwards or backwards, depending on the consequences and criticality of the issue.