Architecture forms the vocabulary of an application’s codebase. My recent post on data loading introduced the concepts that my project uses to solve the problem of displaying customer data. Application architecture is the next level of object-oriented design: instead of designing the behavior of one part of the system, you are concerned with how an entire set of objects interact. Architecture answers the question “Our application is X”.

Software architecture is different from building architecture in that it can change: it is living in a house that can become anything. From a feature development point of view, the ideal is a completely static architecture: every room is the same and the design of each is simple and obvious. New features challenge these assumptions by requiring that you build new rooms that may not exist and whose ultimate utility may not even have been dreamed. The application architecture a project needs to support the features of today could be totally different from the architecture it will need in two years. Application architecture is made up by the team as they go along.

The question I want to investigate in this post is How do you evaluate your architecture? The cost of change is high: if you think your application fundamentally is one thing and then you discover it’s another, this invalidates all the assumptions your code previously worked with. Every team member wants to do things the “right” way and it’s unreasonable to expect synchronize complicated architecture discussions on the team for too long.

Evaluating Architecture

Here are some criteria that I’ve use to understand whether or not a particular architecture is appropriate. These are questions that the team should ask themselves over weeks and months to decide whether the code architecture that the team has is actually working to its best.

Architecture Must Solve Your Problems

Architecture is an answer to the day to day requirements of your application. It should answer the questions of incoming work. One of the key patterns in the Cloud Control Panel is the popover.

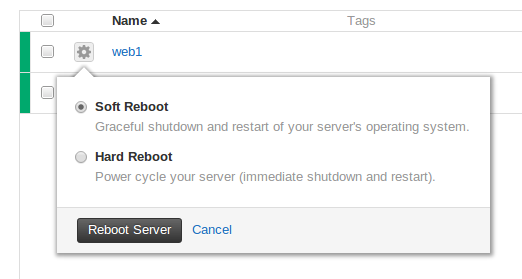

To the user the important thing about this popover is that it lets them reboot their server through our webapp. When working on this feature, developers should ideally spend most of their time exposing reboot specific functionality, not popover specific functionality.

We now have over 100 different popovers on the site. When we began development (two years ago now) we had goog.ui.Popup, which handled placement of the element and hiding when clicking off of it. It didn’t handle the required markup, save/cancel buttons, keeping the popover open after clicking save, or displaying errors if the operation failed. In building the ability to reboot a server, we needed to tackle all these other problems that were marginal to story card (“As a user, I can soft reboot a server.”) – our architecture using goog.ui.Popup did not solve the main problem we set out to solve.

Architecture Must Simplify

A good architecture will remove many details from everyday consideration. The reason that software development introduces abstractions is so that you don’t have to grapple with all the details of everything in your day to day work. Even the most simple Rails application has some insanely complicated details: how does the HTTP server work, how does the database work, how does data get to the controller, how does the browser interact with the webpage in order to load scripts and stylesheets, how does the Linux kernel interact with the network hardware to even get data into your application – we have abstractions to seal these details off from our day to day work.

I don’t pretend that our eventual data loading architecture is simple: it is a solution of a number of rather complicated requirements. Understanding the details of its implementation requires a solid grasp on deferreds, Closure Library moduules, and each of the responsibilities of each given section. However this architecture removes these very complicated problems from day to day consideration. Developers on the team are able to do work without engaging with in this full complexity because every view on the site loads upstream data exactly the same.

Architecture Must Fit Into the Entire Team’s Headspace

Ideally, architecture is simple enough that it can be explained easily and every part of the code follows these concepts. Less good but still okay is a situation where your team has an architecture in transition: “Oh, we used to do X, but now we do it Y”. The key here is that every team member needs to be able to have the same shared understanding of what the architecture means to their day-to-day life. If architecture is in transition, work in an area that uses older patterns might end up refactored to use newer patterns.

The situation you want to avoid is where different parts of the code use radically different architecture. Once I worked on a project that was 7 years old that had been maintained by at least 5 different teams. It was obvious when you looked at a class which team worked on it – and of course my team’s contributions were no different! In this kind of system it becomes a lot harder to make general statements about the application and so work requested by people outside the project becomes harder to fulfill. In order to instrument the entire project to log all upstream requests we had to instrument logging interceptors into multiple places, some of it fairly legacy code.

Concepts Must Match the Code That Surrounds Them

Architecture should “seal” general concepts to existing in general classes. If your architecture forces forces these general concepts to “bubble up” into specific places, something is incorrect with it.

For example, CSRF protection is a very general concept in a web application and all your client-side updates are probably going to have to supply a CSRF token in requests they make through your web application. You wouldn’t expect the UserSettingsView to have code specific to CSRF protection: you’d expect it do deal with things related to displaying user settings. The name of the object implies the responsibilities it should have.

New Behaviors Are Not Architecture

New behaviors are verbs. Architecture are the nouns of the system. Every abstraction has a maintenance overhead: it’s another “thing” for the team to carry around in their collective headspace. It’s really tempting to attach things to existing concept in a codebase. “Oh an X does Y, but we could make it do Z too”. This conflates once-clear concepts and is hard to synchronize across the team as it gets larger: whereas the team once had a shared understanding of X objects as having a limited set of responsibilities, new behaviors make it harder to make general statements about the entire codebase and this lack of team understanding can lead to defects.

I’ve had the most success from deferring architectural choices until you have a large enough sample size to be confident that what you’re building is an abstraction that solves the right problems. Examples are the most powerful argument for the sufficiency or insufficiency of an approach and once you have enough examples you can generalize them into a common code. The cost of making a change to a class that is dependended on by the entire team and used everywhere can be huge. The cost of developing small 1-offs for new “things” is low.

I’ve used subclassing successfully for this. If there’s one table on the site with new behavior (“oh, it collapses when you click on it!”), subclass the old table class and add the new logic in a very specific place (“well, this table is only used for the foobar section, so it’s the FoobarTable”), and extract the common logic when it’s clear that this new behavior actually is a new noun in the system rather than a set of new requirements for one section.

Conclusion

When I was a young programmer back in 2002 (this was during first XP ‘wave’) I talked to my mentor about design and described my ideal system: a set of formally defined mathematical objects with clear interactions between each other – a Platonic universe where these objects existed in their own sense. I got shot down pretty good; my mentor espoused a more agile and gradual approach to object design and this conversation has stuck with me through the years. While I still have a bad habit of referring to approaches as “correct” or “incorrect”, today I tune my sense of the correctness or incorrectness of any given approach to the criteria I’ve described above rather than any sense of mathematical purity.

Architecture is both the most and least useful thing to invest time in. Done well, you can end up with a more expressive codebase that makes it easy to finish features and deliver customer value. Done improperly, you can spend a lot of time on things that deliver only developer value – not that software developers aren’t important, but you need a significant amount of developer value in order to offset time that could have been working on customer features.

Even if these criteria fail, it still may not be worth the time or effort to change. (The “right” decision is often only clear in hindsight.) Good architecture is the product of a collaboration of the entire team working together to extract shared problems into a common set of nouns that support new feature development for the product.